Response to "Skin and Bones"

Vidler, Anthony. “Skin and Bones - Folded Forms from Leibniz to Lynn” Warped Space. Art, Architecture, and Anxiety in Modern Culture. MIT Press, 2001.

The preface depicts Vidler as a theorist with nearly-congruent ideology to that of Greg Lynn. Like Lynn, he describes the Deconstructivist Movement as a reinterpretation and conceptualization of Bataille, which adds complexity through theory and digital manipulation. Instead of a blob, Vidler outlines his process in producing his warped spaces: modernism's psychological culture leading to distortions; and interpretations of intersecting media (intermediary art).

The House of Folds. Vidler begins this section by describing Gilles Deleuze's definition of a fold: "the fold [that joins the soul to the mind without division] is at once abstract, disseminated as a trait of all matter, and specific, embodied in objects and spaces..." (Vidler 218). With the abstraction of folding, Vidler then claims that contemporary architects are in constant mentality of making tangible a thought. To prove such claim, Vidler dissects Deleuze's ideology with his main influences: Gilles Leibniz and John Locke.

Le Maison Baroque

Four windows and a door line themselves along the ground floor;

second story floor has five openings, each hung through with a loosely falling curtain.

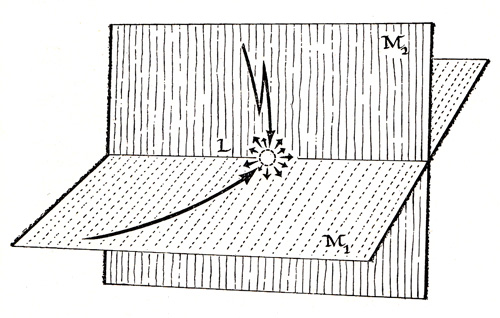

Vidler's claim relates to human perception and its expression. Leibniz's drawing of Le Maison Baroque exemplifies a Baroque House functioning in a similar fashion to the human mind. Leibniz symbolizes the lower floor as the grounded body transmitting knowledge - given by each of the five senses - to the soul in the level above. By nature, humans innately translate tangible information to knowledge; however, the converse of the process is difficult due to the endless number of folds (as explained in psychology by Koestler's bisociation of matrices in The Act of Creation).

Bisociation of Matrices

Two seemingly tangent ideas converge at a "fold"

With John Locke's view of the brain as a camera obscura, the mind is seen as a storage house for direct reflections of the world. Though this mentality seems limiting, Vidler explains that Leibniz asserts that such reflections provide a base to begin transformation and abstraction. The abstraction process would be conducted and diversified through folds of a screen over the reflection. Adding complexity and generating images from a trace arouses new ideas - another derivation of the term fold.

With Leibniz's and Locke's ideas, Vidler delves into the composition of Deleuze's theory. The creation of Deleuzian space matches Leibniz's Baroque House, but diverges by the more fluid and non-uniform nature of the space. Leibniz's spaces do not require a connection between the folded screen and its interiors, but (Vidler 223). Deleuze's lack of connection distinguishes envelopes as independent entities from their contents. In the next section, Vidler elaborates upon the fold by returning to Le Maison Baroque:

The outside may have windows, but they open only to the outside; the inside is lit, but in such a way that nothing can be seen through the "orifices" that bring light in. Joining the two, as we have seen, is the fold, a device that both separates and brings together, even as it articulates divisions acting as invisible go-between and visible matter.Animistic Architecture. Dubbed allegorical surrealism, the idea of surrealism in mathematics and architecture began post-WWII with Marcel Jean's project. "... Jean proposed a hallucinatory landscape of mathematically and anthropomorphically derived forms for a 'Plan of Reconstruction for a European Capital'" (225). The main characteristic to his plan was the inclusion of non-Euclidean forms to break the city grid's purity. Vidler claims that Jean's plans had set the complex and Deconstructivist nature of amorphous form today.

Vidler praises Lynn's thoughts on architecture as "potential evolution to architectire if not the species; they seize on the metaphor nor to end monumentality but to change its formal nature" (226). Vidler entertains the notion of blobs as natural phenomena; that is, blobs are plays of natural permutations. He continues to justify his position by describing the example of Victor Hugo's Elephant of Bastille. The statue itself had the potential for human occupancy (fondly recounted by Gavroche in Hugo's Les Misérables) though the elephant followed no precedent for a habitable structure.

In the conclusion of this chapter, Vidler points out that the act of folding is to join the material and immaterial. The trend of architecture he proposes is the imputation of animate life to inanimate animation (228), and that the process of the fold becomes the form.

From instances where folding becomes a connection between two forms or ideas to the virtual world in which the action of folding becomes the form itself, we are inspired by the almost limitless contemporary means that yield us to go well beyond 'formal design'.

ReplyDeleteThe idea of architecture and the senses, particularly the way that the lower level acts as a channel to the upper floors, reminds me of Bloomer and Moore's "Body, Memory and Architecture." In it they discuss how the different levels of the house yield different experiences; basement is subconscious, main floor is memory, and the attic is the dream. In a sense it could create destabilization when a buildings structure is morphed, particularly when different programs are folded into one another.

ReplyDelete